Sirach

|

Part of a series

of articles on the |

|---|

| Tanakh (Books common to all Christian and Judaic canons) |

| Genesis · Exodus · Leviticus · Numbers · Deuteronomy · Joshua · Judges · Ruth · 1–2 Samuel · 1–2 Kings · 1–2 Chronicles · Ezra (Esdras) · Nehemiah · Esther · Job · Psalms · Proverbs · Ecclesiastes · Song of Songs · Isaiah · Jeremiah · Lamentations · Ezekiel · Daniel · Minor prophets |

| Deuterocanon |

| Tobit · Judith · 1 Maccabees · 2 Maccabees · Wisdom (of Solomon) · Sirach · Baruch · Letter of Jeremiah · Additions to Daniel · Additions to Esther |

| Greek and Slavonic Orthodox canon |

| 1 Esdras · 3 Maccabees · Prayer of Manasseh · Psalm 151 |

| Georgian Orthodox canon |

| 4 Maccabees · 2 Esdras |

| Ethiopian Orthodox "narrow" canon |

| Apocalypse of Ezra · Jubilees · Enoch · 1–3 Meqabyan · 4 Baruch |

| Syriac Peshitta |

| Psalms 152–155 · 2 Baruch · Letter of Baruch |

|

|

Sirach, by the Jewish scribe Ben Sira of Jerusalem, also known as Wisdom of Jesus son of Sirach, the Wisdom of Ben Sira, or Ecclesiasticus, is a work from the early second century BC, originally written in Hebrew.

The book was not accepted into the Hebrew Bible, as a result the Jewish community choose not to preserve it in the original Hebrew text, and it exists now only in the Greek translation of the original. Sirach is occasionally quoted in the Talmud and works of rabbinic literature (as "ספר בן סירא", e.g., Hagigah 13a). Despite its rejection from the Jewish cannon, it was included in the Septuagint (the 2nd century BCE translation of the Hebrew Bible into Greek) and is accepted as part of the Christian biblical canon by Catholics, Eastern Orthodox, and most Oriental Orthodox but not by most Protestants, and is listed in among the Deuterocanonical books in Article VI of the Thirty-Nine Articles of the Church of England[1]. The Greek Church Fathers also called it "The All-Virtuous Wisdom," while the Latin Church Fathers, beginning with Cyprian[2], termed it Ecclesiasticus because it was frequently read in churches, leading to the title liber ecclesiasticus (Latin and Latinised Greek for "church book").

In Egypt, it was translated into Greek by the author's grandson, who added a prologue. The Prologue to Ben Sira is generally considered the earliest witness to a canon of the books of the prophets, and thus the date of the text as we have it is the subject of intense scrutiny.

Contents |

Title and versions

The Book Ben Sira ("ספר "בן סירא) was originally written in Hebrew, and is also known as Proverbs of Ben Sira (משלי בן סירא) or Wisdom of Ben Sira (חכמת בן סירא).

The Greek translation was accepted in the Septuagint under the (abbreviated) name of the author: Sirakh (Σιραχ). The final chi is not to be pronounced; it simply points to the foreign origin of the name and shows that the noun cannot be declined in Greek. Some Greek manuscripts give as title Wisdom of Jesus, son of Sirakh or in short Wisdom of Sirakh.

The old Latin versions were based on the Septuagint, and simply transliterated the Greek title in Latin letters: Sirach.

In the Vulgate the book is called Liber Iesu filii Sirach. The neo-Vulgate uses the title given by the early Latin Fathers: Ecclesiasticus, literally (belonging) to the Church, because of its frequent use in Christian teaching and worship.

Today it is more frequently known as Ben Sira or simply Sirach. ("Ben Sirach" should be avoided because it is a mix of the Hebrew and Greek titles.) The name Siracides, of more recent coinage, is also encountered, especially in scholarly works.

Author

Ben Sirah, a Jewish scribe who had been living in Jerusalem, may have authored the work in Alexandria, Egypt circa 180–175 BC, where he is thought to have established a school.[3]

Translation and dating of the work

The Prologue to Ben Sira is generally considered the earliest witness to a canon of the books of the prophets. Thus the date of the text as we have it has been the subject of intense scrutiny.[4][5][6]

The Greek translator states in his preface that he was the grandson of the author, and that he came to Egypt in the thirty-eighth year of the reign of "Euergetes". This epithet was borne by only two of the Ptolemies. Of these, Ptolemy III Euergetes reigned only twenty-five years (247-222 B.C.) and thus Ptolemy VIII Euergetes must be intended; he ascended the throne in the year 170 BC, together with his brother Philometor, but he soon became sole ruler of Cyrene, and from 146 to 117 held sway over all Egypt. He dated his reign from the year in which he received the crown (i.e., from 170). The translator must therefore have gone to Egypt in 132 BCE.

Considering the average length of two generations, Ben Sira's date must fall in the first third of the Second Century BCE. Furthermore, Ben Sira contains a eulogy of "Simon the High Priest, the son of Onias, who in his life repaired the House" (50:1). Most scholars agree that it seems to have formed the original ending of the text, and that the second High Priest Simon (died 196 BC) was intended. Struggles between Simon's successors occupied the years 175–172 BC and are not alluded to in the book, nor is the 168 BC persecution of the Jews by Antiochus IV Epiphanes.[7][8]

Ben Sira's grandson was in Egypt, translating and editing after the usurping Hasmonean line had definitively ousted Simon's heirs in long struggles and was finally in control of the High Priesthood in Jerusalem. Comparing the Hebrew and Greek versions shows that he altered the prayer for Simon and broadened its application ("may He entrust to us his mercy"), in order to avoid having a work centered around praising God’s covenanted faithfulness that closed on an unanswered prayer.[6]

Texts and manuscripts

The work of Ben Sira is presently known through various versions, which scholars still struggle to disentangle.[9]

The Greek version of Ben Sira is found in many codices of the Septuagint.[9] An English version of the Septuagint text can be found here.

In the early 20th century several substantial Hebrew texts of Ben Sira, copied in the eleventh and twelfth centuries AD, were found in the Cairo geniza (a synagogue storage room for damaged manuscripts). Although none of these manuscripts is complete, together they provide the text for about two-thirds of the book of Ben Sira. According to Frederic Kenyon, this shows that the book was originally written in Hebrew. (Our Bible and the Ancient Manuscripts. Rev. by A.W. Adams. London: Eyre & Spottiswoode, 1958. 83.) That Sirach was originally written in Hebrew may be of some significance for the biblical canon. The book was accepted into the canon of the Old Testament by Catholicism and Eastern Orthdoxy but not by Judaism or Protestantism.

In the 1950s and 1960s three copies of portions of Ben Sira were found among the Dead Sea Scrolls. The largest scroll was discovered at Masada, the famous Jewish fortress destroyed in 73 AD. The earliest of these scrolls (2Q18) has been dated to the second part of the 1st century BC, approximately 150 years after Ben Sira was first composed. These early Hebrew texts are in substantial agreement with the Hebrew texts discovered in Cairo, although there are numerous minor textual variants. With these findings, scholars are now more confident that the Cairo texts are reliable witnesses to the Hebrew original.

Contents

The Book of Ben Sira is a collection of ethical teachings. Thus Ecclesiasticus closely resembles Proverbs, except that, unlike the latter, it is the work of a single author, not an anthology of maxims drawn from various sources. Some have denied Ben Sira the authorship of the apothegms, and have regarded him as a compiler.

The teachings are applicable to all conditions of life: to parents and children, to husbands and wives, to the young, to masters, to friends, to the rich, and to the poor. Many of them are rules of courtesy and politeness; and a still greater number contain advice and instruction as to the duties of man toward himself and others, especially the poor, as well as toward society and the state, and most of all toward God. These precepts are arranged in verses, which are grouped according to their outward form. The sections are preceded by eulogies of wisdom which serve as introductions and mark the divisions into which the collection falls.

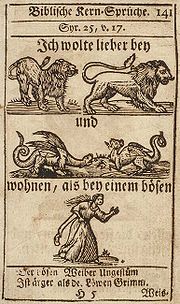

Wisdom, in Ben Sira's view, is synonymous with the fear of God, and sometimes is identified in his mind with adherence to the Mosaic law. The maxims are expressed in exact formulas, and are illustrated by striking images. They show a profound knowledge of the human heart, the disillusionment of experience, a fraternal sympathy with the poor and the oppressed, and an unconquerable distrust of women.

As in Ecclesiastes, two opposing tendencies war in the author: the faith and the morality of olden times, which are stronger than all argument, and an Epicureanism of modern date. Occasionally Ben Sira digresses to attack theories which he considers dangerous; for example, that man has no freedom of will, and that God is indifferent to the actions of mankind and does not reward virtue. Some of the refutations of these views are developed at considerable length.

Through these moralistic chapters runs the prayer of Israel imploring God to gather together his scattered children, to bring to fulfilment the predictions of the Prophets, and to have mercy upon his Temple and his people. The book concludes with a justification of God, whose wisdom and greatness are said to be revealed in all God's works as well as in the history of Israel. These chapters are completed by the author's signature, and are followed by two hymns, the latter apparently a sort of alphabetical acrostic.

Influence in the Jewish liturgy

Ben Sira was used as the basis for two important parts of the Jewish liturgy. In the Mahzor (High Holy day prayer book), a medieval Jewish poet used Ben Sira as the basis for a poem, KeOhel HaNimtah, in the Yom Kippur musaf ("additional") service for the High Holidays. Recent scholarship indicates that it formed the basis of the most important of all Jewish prayers, the Amidah. Ben Sira apparently provides the vocabulary and framework for many of the Amidah's blessings. Many rabbis quoted Ben Sira as an authoritative work during the three centuries before the advent of Yavneh.

In the New Testament

Some people claim that there are several allusions to the book of Sirach in the New Testament. These include The magnificat in Luke 1:52 following Sirach 10:14, the description of the seed in Mark 4:5,16-17 following Sirach 40:15, Christ's statement in Matthew 7:16,20 following Sirach 27:6 and James 1:19 quoting Sirach 5:11.[10]

The distinguished patristic scholar Henry Chadwick has claimed that in Matthew 11:28 Jesus was directly quoting Sirach 51:27,[11] as well as comparing Matthew 6:12 "And forgive us our debts, as we forgive our debtors." (KJV) with Sirach 28:2 "Forgive your neighbor a wrong, and then, when you petition, your sins will be pardoned."[11]

Messianic interpretation by Christians

The catalogue of famous men in Sirach contain several messianic references. The first occurs during the verses on David. Sir 47:11 reads “The Lord took away his sins, and exalted his power for ever; he gave him the covenant of kings and a throne of glory in Israel.” This references the covenant of 2 Sam 7, which pointed toward the Messiah. “Power” (Heb. qeren) is literally translated as horn. This word is often used in a messianic and Davidic sense (e.g. Ezek 29:21, Ps 132:17, Zech 6:12, Jer 33:15). It is also used in the Benedictus to refer to Jesus (“and has raised up a horn of salvation for us in the house of his servant David”).[12]

Another messianic verse (47:22) begins by again referencing 2 Sam 7. This verse speaks of Solomon and goes on to say that David’s line will continue forever. The verse ends telling us that “he gave a remnant to Jacob, and to David a root of his stock.” This references Isaiah’s prophecy of the Messiah: “There shall come forth a shoot from the stump of Jesse, and a branch shall grow out of his roots”; and “In that day the root of Jesse shall stand as an ensign to the peoples; him shall the nations seek…” (Is 11:1, 10).[13]

Another way Sirach is interpreted messianically is its use of personified Wisdom. In Sirach Wisdom is personified twice, in chapters one and 24. Wisdom is explicitly said to be eternal: “From eternity, in the beginning, he created me, and for eternity I shall not cease to exist.” (24:9) At Sir 1:4 the genesis of Wisdom is described much as it is at Prov 8:22. Like Prov 8, Sir 24 has many parallels to Col 1:15. Wisdom tells us that she “came forth from the mouth of the Most High, the first-born before all creatures.” (Sir 24:3a) This statement is similar to Christ’s being the Word, and the “first-born of all creation”. (Col 1:15b) At Sir 24:19 Wisdom tells her listeners to “Come to me”, which, it has been noted, is similar to Christ’s saying “Come to me” at Mt 11:28. Like Jesus the Messiah, Wisdom also keeps souls from sin (Sir 24:22).

Notes

- ↑ "Thirty-Nine Articles" Wikisource

- ↑ Testimonia, ii. 1; iii. 1, 35, 51, 95, et passim

- ↑ Coogan, Michael (ed.) (2001) "Apocrypha" The New Oxford Annotated Bible: With the Apocryphal/Deuterocanonical Books Oxford University Press, New York, pp. 100-101, ISBN 0-19-528478-X

- ↑ Williams, David Salter (1994) "The Date of Ecclesiasticus" Vetus Testamentum 44(4): pp. 563-566

- ↑ DeSilva, David Arthur (2002) "Wisdom of Ben Sira" Introducing the Apocrypha: Message, Context, and Significance Baker Academic, Grand Rapids, p. 158, ISBN 0-8010-2319-X

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Guillaume, Philippe (2004) "New Light on the Nebiim from Alexandria: A Chronography to Replace the Deuteronomistic History" Journal of Hebrew Scriptures 5: Section: 3. The Date of Ben Sira

- ↑ 1 Maccabees 1:20-25, see "Polyglot Bible. 1 Maccabees.". http://www.sacred-texts.com/bib/poly/ma1001.htm. Retrieved 2009-08-05.

- ↑ "How the City Jerusalem Was Taken, and the Temple Pillaged. As Also Concerning the Actions of the Maccabees, Matthias and Judas; and Concerning the Death of Judas" In William Whiston's translation of Flavius Josephus The Wars of the Jews

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Stone, Michael E. (ed.) (1984) Jewish Writings of the Second Temple Period: Apocrypha, Pseudepigrapha, Qumran, sectarian writings, Philo, Josephus Van Gorcum, Assen, Netherlands, p. 290, ISBN 0-8006-0603-5

- ↑ Scripture Catholic - Deuterocanonical Books In The New Testament

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Henry Chadwick, (2001) The Church in Ancient Society: From Galilee to Gregory the Great Clarendon Press, Oxford, England, page 28, ISBN 0-19-924695-5

- ↑ Skehan, Patrick (1987) The Wisdom of Ben Sira: a new translation with notes (Series: The Anchor Bible volume 39) Doubleday, New York, p. 524, ISBN 0-385-13517-3

- ↑ Skehan, Patrick (1987) The Wisdom of Ben Sira: a new translation with notes (Series: The Anchor Bible volume 39) Doubleday, New York, p. 528, ISBN 0-385-13517-3

Sources

- Beentjes, Pancratius C. (1997) The Book of Ben Sira in Hebrew: A Text Edition of All Extant Hebrew Manuscripts and a Synopsis of All Parallel Hebrew Ben Sira Texts E.J. Brill, Leiden, ISBN 90-04-10767-3

- Toy, Crawford Howell and Lévi, Israel (1906) "Sirach, The Wisdom of Jesus the Son of" entry in the Jewish Encyclopedia

- Amidah, entry in (1972) Encyclopedia Judaica Jerusalem, Keter Publishing, Jerusalem, OCLC 10955972

External links

- Sirach (Ecclesiasticus) - Latin Vulgate with Douay-Rheims version side-by-side

- "Ecclesiasticus" Catholic Encyclopedia

- Ecclesiasticus, all chapters, full text, searchable

- Sirach - Bibledex video overview

| Preceded by Book of Wisdom |

Roman Catholic Old Testament | Followed by Isaiah |

| Eastern Orthodox Old Testament | ||

| see Deuterocanon |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||